Jared Alderman:

– Today on the podcast, we have LuckyChewy back. LuckyChewy has recently released an app called Khemset. It is an intuition trainer.

So, we got together on rather short notice to record this episode for you. And in the episode, we cover things like intuition, how we affect people’s behavior at the table, the physics of what makes this more or less likely or possible. I push back on some of the things that Chewy mentioned in his post, and I steelman some of his arguments as well.

I really enjoy talking to Chewy. He’s a really brilliant mind and a very open person, and I appreciate all that he does to push us into uncharted territory in the space of poker performance.

Alderman: Chewy, welcome. Thank you so much for doing this and on short notice.

Andrew Lichtenberger: Thanks for having me!

Alderman: So just jumping right in as some preamble—you recently created and released an app called Khemset. This is like an intuition trainer. Is that a fair thing to say?

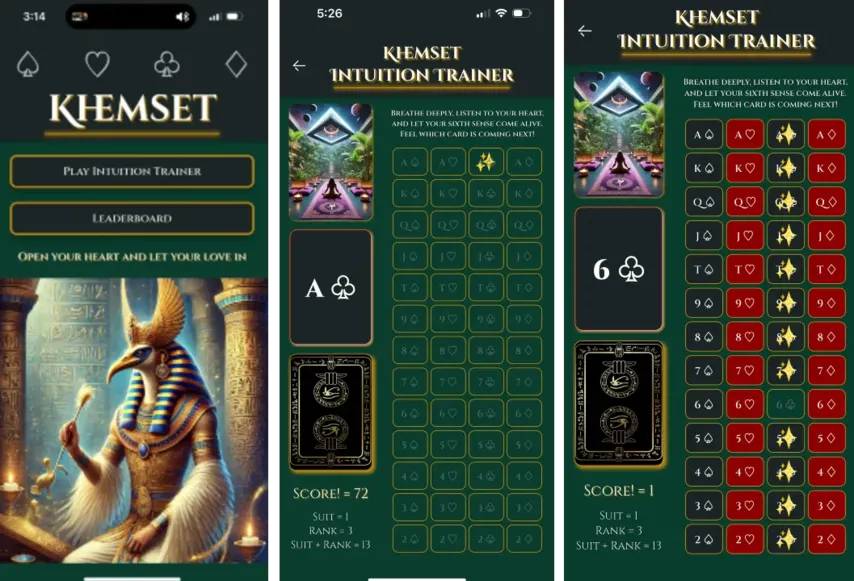

Lichtenberger: Yeah. So, it's a 52-card playing deck, randomly shuffled, and you're scored based on how well you select cards accurately. You get one point for the suit being right, three points for the correct rank, and then 13 for a perfect match.

There's no dynamic scoring, so your probability of being correct goes up after each subsequent guess because you can't guess a card with a 0% probability. So if you take 10 picks—whatever those 10 picks are—you can't pick those cards again.

Alderman: So it's not also a memory trainer?

Lichtenberger: It's not. Although that would be interesting. I did actually really pursue memory as a child. I don’t know why, but I found it really interesting. I read as many books as I could get my hands on. And yeah, I do have a pretty solid memory, so maybe there’s something to that as well.

Alderman: I don’t know if we talked about this before, but I did memory competitions. – I did the USA World Memory Competition.

Lichtenberger: I wish we could compete! I’d probably get crushed.

Alderman: Would be fun, probably. Depending on the thing. The thing about memory training is, if it's not a thing that I have a system in, I could probably come up with a system fairly quickly.

Lichtenberger: You do the thing where you put stuff in your childhood room and all that?

Alderman: Memory palace – yeah, sure.

Anyhow, so you released this app, and then to announce it—or something—you posted something on Twitter explaining kind of the rationale behind it. Like why this might be worth someone’s time. Varied reactions to this post, I would say.

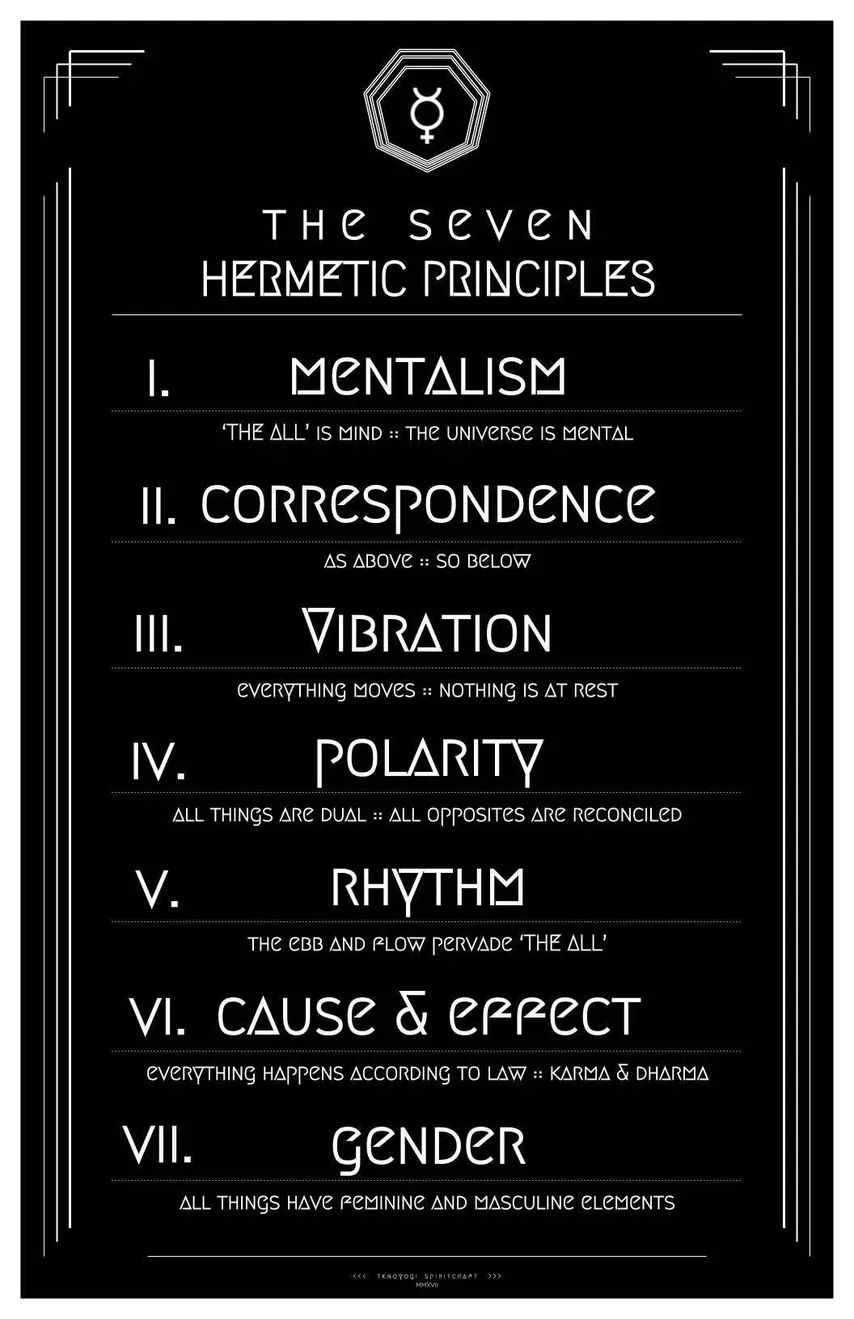

Khemset Primer: How Vibratory State Shapes Poker Outcomes

1. The human body as an electromagnetic system

The heart and brain emit measurable electromagnetic fields. The heart’s field is the most powerful. It can be detected several feet away. Electromagnetic field pattern shifts with changes in emotional states and nervous system tone.

Key takeaway: You’re always broadcasting a vibratory state into your environment.2. Coherence vs. incoherence

Coherent states: calm presence, gratitude, smooth, stable EM patterns.

Incoherent states: stress, fear, ego grasping, chaotic, unstable EM patterns.

Why it matters: Coherence improves cognitive function, intuition, and emotional regulation. Coherent players are most likely to influence and entrain others at the table.3. The Observer Effect (Quantum Foundation)

In quantum physics, observation collapses wave functions into measurable outcomes. The observer is not separate from the observed.

Implication in probabilistic environments like poker: Your state of observation interacts subtly with unfolding events, especially human decisions.4. How vibratory state affects poker through:

- Better perception of timing and flow

- Increased ability to recognize subtle cues

- Improved decision quality under pressure

- Positive influence on table dynamics (entertainment)

- Less self-sabotage from emotional contraction

Result: What some will call "luck" is often a byproduct of coherence—aligning with better opportunities and outcomes.

5. What does it not mean?

- You cannot force outcomes or override variance.

- You cannot manifest aces or control randomness.

- You can, however, tune your system to interact more favorably with a complex probabilistic field of poker.

So I think I’ll kind of tell you what I believe you to be saying, and you can then correct me.

I do believe that part of what might be confusing about this is the use of the term probability. Probability in statistics really is just a representation of ignorance, right?

So when I say, “Well, if I reach into a jar, let’s say there are six coins, I put number one through six on coins, throw them in a jar, and I tell you to reach in,” and I say, “There’s a one in six chance that you grab the number three.”

Depending on your description of reality, it could be that there’s a one in six chance given what we know, right? Like, you could know much more. Maybe the jar is see-through, and I’m blind, and I don’t know. You now know where it is, right?

As soon as I give you the requisite knowledge, probability becomes less "probability." Because, people will talk about not being able to affect probabilities. And it’s like—yeah, but if you can learn, the more that you learn, the less things are probability. The more things are just navigating the space as you understand it to be.

If I’m driving in a city that I don’t know, and I’m like, “Well, there are three turns here, and I know my house is down one of them. I have a one in three chance.” Me knowing which route gets me home is not me affecting probabilities. It is me having knowledge that allows me to navigate the world in a different way and respond to the world in a different way.

So I don’t know if this gets to a bit of the heart of what you’re saying. It seems to me that you seem to be putting forth this idea that we are more connected with the world than we think we are. We have more data from reality than we think that we do. And the more you become in tune with this data that you have access to, you can respond more appropriately to the environment you might find yourself in.

Is that something like what you’re saying?

Lichtenberger: I think that’s certainly a fair way to describe it. It’s probably not the way I would have thought to describe it. Someone asked about this on X, and I responded basically that I don’t think I’m special in any way. I’m not doing anything necessarily that anyone else isn’t.

My thought is just that the way that we as humans interface with our environments—and poker especially, because it’s such a sort of rich, interesting experience of psychology and emotion and strategy and all the rest of it—there are these subtle impacts that we as humans have on the game and the probabilistic nature of it in terms of how our opponents are going to respond to us. And then yeah, perhaps some more esoteric things, like card distribution or what have you.

So yeah, my thought is essentially that we’re all doing this without trying. It’s just kind of built into who we are, and what the nature of the game is, and what it allows for. And my fascination is just in having, obviously, many experiences playing poker over the years—just trying to gain some greater levels of insight and clarity into what contributing factors to that are. And that’s what’s led me toward this exploration of coherence. And yeah, certainly an interesting topic to discuss.

Alderman: Yeah. So let’s run through the spectrum—let’s break these—because I can depict kind of three categories of descriptions of things. Some that I think almost everyone would be on board with, some that I think people might be a little skeptical of, and then some that I think are probably the most esoteric. And I think it’s kind of interesting to flag all these as unique.

Because everything you’re talking about—the subtle ways in which we interact and cause different reactions from people—like one of the things you mentioned in your post about coherence and incoherence I think is really true. There’s something really palpable about being the steadiest presence at the table. And I mean, there are biological and evolutionary reasons for this, but the way that it affects the minds of the people you’re competing against—the way that we have really strong intuitions on who to follow, who to lead, etc.—that’s that idea of entrainment.

Lichtenberger: The stereotypical example, to me, is like prime Phil Ivey. He kind of just bent reality with his will. Not that he doesn’t do it anymore, but it was so heightened in that era where he was just the top dog, you know?

Alderman: And I think we might describe this obviously a bit differently, but very few people, I think, would debate that there’s something here, right? Like, there’s clearly something to your presence at the table and the way that it affects people and causes things to go in your favor.

And then in between the most esoteric things and something like this is this idea of being in flow with reality. And this is where I feel fairly agnostic—myself personally. Being in flow with reality, in the realm of luck.

Lichtenberger: So for example, it might be that you can sense, in some sense, that you’re about to lose this next hand or something like that. There might be something that you can pick up on—be it the actual distribution of the cards that are about to come your way, the actual...

Like, I can talk about how I believe this might fit with our picture of physics and where things lead. But to be able to detect distribution of outcomes—not that you can change it—but to be able to detect it as a shift that might be happening. Yes. I mean, I would say based on my experience playing poker, I didn’t necessarily start off with this particular ability, but I feel over the years, there are just these little inklings that you get. And sometimes they are just noise, and sometimes they are signal.

But no, I do believe that there is some method to this madness where you can sense a likely probabilistic outcome. And I don’t know exactly what that foresight or that clairvoyance is. I don’t know if it’s like we’re in a multiverse and you’re connecting to—or you sense that a parallel reality is inbound.

That creates a whole other set of interesting questions. Like, can you shift that? How is that transformed? Is it easier? Is it challenging? I don’t know.

Alderman: Yeah. And I think it’s worth saying—for people who don’t know me—I am as skeptical as people come. I think it’s worth saying I consider myself very scientifically literate. And the idea that humans have different sensory perceptions than the ones we understand ourselves to have is, at best, scientifically foggy.

If you go looking into the research, there is far from conclusive scientific evidence that people don’t have some level of extrasensory perception when it comes to all kinds of things that they test. And I say that because I think part of the pushback people give is that this sounds categorically like... I don’t know where you stand on this, but to me, zodiac signs are clear nonsense. I think there’s nothing to zodiac signs. I think it’s clear nonsense.

Lichtenberger: Yes, me too.

Alderman: But whether or not you feel that way, I think people put all of these things into the same bucket. And I think there is a point where, if you consider yourself scientifically literate, it would behoove you to know which things we actually have strong evidence for, and which things we don’t—and some of those things for which we really have mixed evidence.

And it really does seem that people can beat chance on simple tests of “I’m holding a card—what’s on it?” They do these kinds of extensive tests, and there have been many cases of people seemingly beating chance.

We know space—the experience of space—is emergent. It’s not foundationally real. It’s not the fundamental fact of reality.

So this sense that we are far removed from things in our perception—like, the best scientists today know that’s not really what’s happening. This is a representation of reality that our minds concoct for us to be able to navigate space—based probably on evolutionary primacy, the importance of it.

But we know that space is not quite what it seems. And that our experience of three-dimensional space is probably not what it is.

And I think once you grant—even without getting that deep—if that’s true, it opens all kinds of questions for what is the world we’re actually inhabiting, and all kinds of moments, you know?

Lichtenberger: Well, I would say the thing that would logically follow is that maybe time is also not what we think it is, right?

And that maybe can shed some light on the idea that having these insights, feelings, inclinations—what have you—towards likely or unlikely probabilistic outcomes… Well, if time is somewhat illusory and maybe a bit less linear than we think it to be, it could reason that there is a plausible way to connect with the “future” in some way. Again, I don’t know exactly how that works.

That’s part of my interest in sharing this. I’m kind of like, “Hey guys, some interesting stuff is happening for me in poker that I’ve observed. Anyone else find this interesting? Anyone have any insights?”

Alderman: To your point, this is also an open discussion on the farthest reaches of where we’re pushing science right now. We do not know if time itself is fundamental or not. There’s Carlo Rovelli, I think is his name—there are tons of physicists I could name who are strongly in the camp of “time is not fundamental.” Again, it’s an emergent phenomenon. It’s something that we experience, but it’s not fundamentally real. It’s not something that’s “happening out there,” if you will. It is very much something that seems to be happening “in here,” from this perspective. Now, there are physicists who disagree, but it’s far from closed.

And if you sit long enough on meditation retreats too, you can have experiences of spaceless, timeless states. It’s hard because without having such an experience, the intuition of “what do you mean there’s no space and time” can be like, “How could that be true?” But if you do, you can have those experiences. They’re on offer. Psychedelics can give you this as well.

Lichtenberger: And dreams.

Alderman: Sure. That’s a good point. Dreams.

Lichtenberger: And if I may just interject quickly—this idea of things kind of not being “out there.” I’ve definitely taken a liking to Hermetic philosophy over the years, and one of their core tenets is “all is mind.” There really is no “out there.” It appears as such, but it’s all just a projection of one’s own consciousness. I think that’s a really interesting idea to play with.

Alderman: Well, I still believe that there is an "outside" and that our consciousness interprets it, but does not create it. I sense space, although it is an illusion. However, it is an illusion – a reflection of something real.

Lichtenberger: If it is the case that this experience is the only thing happening in the universe—let’s just say that’s the case—that is still something. That is still a description of reality that is more or less accurate. Either that’s the case—that there’s just this experience, just this. What’s that philosophy? Solipsism?

Alderman: So I guess if I were to now voice some of the criticisms, I think there are some things in your post that strike me as very gratuitous interpretations of certain pieces of scientific evidence—unnecessary leaps. I think you and I land in the same camp on a lot of things. I think how we get there is vastly different.

And part of the reason—if I may voice all of my staked interest in this—part of the reason I’m interested in having this conversation is because I feel deeply invested in convincing people that there’s more to their experience than they give it credit for.

Lichtenberger: We align there.

Alderman: So for example, this interpretation of the observer effect in quantum mechanics—I think this is not a totally accurate interpretation of what the observer effect is in quantum mechanics. The observer effect, as we understand it—or at least as I understand it—really implies nothing, and I don’t know if this is what you were saying. But it implies nothing special about conscious experience.

Lichtenberger: Where, if the Hermetic idea that “all is mind” holds weight, then everything is conscious—it’s an aspect of consciousness. I don’t know. I can’t prove that. I’m inclined—I lean in that direction. But I see how it’s a bit risky, maybe, to wade into the waters of quantum physics when I am certainly not an expert in the topic. And I see how your point is totally valid—like, misrepresenting the conclusions that have been drawn to justify these more esoteric ideas.

Alderman: I think the electromagnetism thing too—I have a qualm with this idea of the human heart having an electromagnetic field. Because if we’re going to talk about the electromagnetic field of human beings...

So, for those who don’t know, I was an EOD tech. I was an Explosive Ordnance Disposal technician. So this, as a feature of reality, mattered to my job. How electromagnetic currents work—where they’re safe, where they’re not, how they affect the world around them—was quite important to doing what I did. And the electromagnetic field of a human is something like 10 to the 111th weaker than the ambient electromagnetic field anywhere. So it’s this tiny, tiny force. And any device that can measure it can only do so by zeroing out the ambient noise. So it can only detect it by zeroing things out. And I guess this is where I’d be curious if that changes anything in your perception of the relevance of the human electromagnetic field.

Lichtenberger: Yeah, that’s understandable. I guess the question I would ask in response is: various devices that have tried to measure or identify the electromagnetic field of humans have not ranked it particularly high in terms of impact. But do we know what the impact is on other humans in terms of what that feeling will be?

Because I know that—what is it—like 70% of interactions are non-verbal, body-language based? You can get a sense of people.

Alderman: And the answer is: not at all. Like, we have no—human beings have no sense for magnetic north as a feature of their nervous system. And this has been tested. Interesting studies have been done to try to give people a sense of magnetic north, actually. People have worn belts that vibrate in the direction of magnetic north, constantly. And they wear them for some long period of time—trying to actually train their nervous system to develop a new sense for magnetic north.

But if you were just a brain with eyes—a human brain with eyes—you would never be able to see. Because the only way we detect sight, or at least our best guess of it right now, is by interacting in the world and getting feedback on it.

Lichtenberger: Do you think the impact of the electromagnetic field of a human being—when engaged in a game like poker, where it's highly competitive and you're in close proximity—would have any differences compared to the way it was studied in these other areas?

Alderman: I think almost certainly not, just because we don’t seem to have a sense of electromagnetism as people.

Now, I don’t think you have to reach there. Like, there could be pheromones. There could be all kinds of things that seem imperceptible to your conscious mind that are being affected and picked up on.

We know that people have these pupillary dilations, right? That mean a lot to someone's internal experience. More importantly, putting it all together—you could be sensing a lot and giving off a lot in your state, and that could be detected. We are very good detectors of people’s emotional states. We’re very social creatures.

Lichtenberger: What's the science behind that, I guess?

I think we can just go to the senses we have—it’s what we can see, what we can hear, what we can smell. Smell is a really big one. Like I said, pheromones play a really big role in this.

What about online? I’ve played a lot of online poker, less so in recent years—but over the course of my career, that felt sense of where someone’s at—it just comes through the screen, just in the same way that it does on the live table.

Alderman: So I have that feeling. I agree with this description. I really do think human beings are just incredible aggregators of information. I think we’re very good at doing something a lot—building a model of a mind somewhere else, taking in the information as we see it, and understanding how more or less likely something is.

Like, for myself, as someone who has spent much of their life in a very contracted mental state—very mentally contracted—and going through long meditation practices, and really feeling what it’s like to release that contraction in your mind. When I say people who are in an open mental state, I think many people don’t understand that there’s a very real subjective difference. Like, there’s an incredibly real subjective difference between what it’s like to be tense and tight and almost literally tunnel-visioned in every moment of your life—versus not.

And the more open you are, the more things you’re doing, you’re picking up on an insane amount of information from moment to moment, and really just letting your creative and intuitive mind put it all together for you.

Alderman: Say a few words about the sick heater you're on, just because I know people are going to be seeing you in all these events, and we're talking about this, and they're going to want to hear about it.

Lichtenberger: So, it's really funny—I had the biggest score of my career in December 2023 at the WPT Wynn Championship for $2.8 million. I got third.

And then I basically just lost for a year and a half. I had some scores in between, but not enough to cover the losses of the buy-ins. And then boom—you just snap your fingers, and in like a week or two, it’s all back, and then some. It’s just amazing how that type of stuff happens.

And you know, as it were, relating it to some of these Chem ideas, I do think there were some things I can hold myself accountable and responsible for that led to the downswing and the subsequent upswing.

One of which was that I’ve had a very on-and-off relationship with caffeine as it relates to poker. I think there are some neurocognitive benefits, but it does make me a bit jittery, and I think it decreases my ability to kind of slow down and trust my intuition.

Which I think—in poker—you really have to play to your strengths. And there are just different styles that people have, and that’s clearly one of my strengths, at least in my own opinion. It’s funny—actually, a lot of people have told me over the years, “Oh, you're so great at math. You're such a nerd wizard.” And I'm like, “I guess,” I mean, but that's not actually how I see my greatest strength to materialize.

So anyway, I kind of spent some time going into this summer thinking, “How am I going to approach playing?” Obviously, caffeine has some benefits in these long stretches. So I was like, “Well, maybe if I just play a little bit less, focus on some of the bigger tournaments, and get rid of it—maybe use it on off days—then it would help me.”

So yeah, I don't know how much of a role that played, but I did sort of give it up a few weeks in advance of the series. And now I can kind of have it on some off days and not feel that it's habit-forming or whatever. But yeah, I do think that that at least appears to play somewhat of a positive role.

Beyond that—yeah, I mean, you just get good cards and win flips, and it’s going to be a nice ride in tournament poker.

Also, my wife is eight months pregnant, as I’ve told you.

Alderman: You know, I do a lot of performance coaching, and I'm often put in this position—maybe I feel it myself, but sometimes explicitly asked—to answer: “Why is this worth doing?” If you do performance coaching with me, it’s very open. I don't really come in with, “Get better at these things.” It's very much just like, “Well, how do we live a happier life? How do we take care of ourselves better?”

And I don’t know. But I know that when I’ve been in phases of feeling like I’m taking the best care of myself, I feel like I’m playing my best.

Lichtenberger: Yeah, I mean, I think that makes a lot of sense. You're sort of using your own agency to better your life. And if you're more comfortable on and off the table, how can that not positively impact you—and holistically everything you do—poker results, relationships, and otherwise?

Alderman: Well, it's strange to me, but it's undeniable.

Do you have a name for your daughter yet, by the way?

Lichtenberger: Sedona.

Alderman: I love that. I'm like—I’m such a... I love babies. I have two kids.

By the way, I wanted a daughter, but my son was born first. My daughter came later.

Girls—they mature so much faster. Having a boy and a girl made it really obvious that they just mature quicker. And I don't know how to describe it. The sense of agency you get from a little girl is drastically higher than you get from a little boy.

What’s funny is the data actually bears this out too. If you look at childhood traumas and their impacts on different genders, it affects men way more than women in terms of life outcomes.

Lichtenberger: It’s interesting, because that would, to me, indicate that men are more sensitive.

Alderman: Oh, yeah. I think there’s a lot of evidence for that—that men are more porous to reality.

Lichtenberger: I don’t think that's a perception that society would have if you just asked them bluntly.

Alderman: No. It’s one of the things I’m honestly most passionate about—this myth of male strength. This myth of male endurance and toughness.

Young boys need—in my experience—more caring. Like, more attending to. More gentleness. More from the get-go. I could just—I have to measure myself. This is part of the particulars of my kids, obviously, but again, the data does bear this out at the societal level. I have to measure myself quite carefully with my son. He can get his feelings hurt really easily. My daughter is just a tank. I can tell her, “Just sit down. I need to change your diaper,” and she just thinks it’s hilarious.

If I were to talk that way to my son, he would just have a breakdown.

Yeah, it's fascinating. And like I said, it's fascinating when you look at all the data on this. You can just see that there's a real epidemic of—I think—young boys not being cared for in the way that they need.

Lichtenberger: I have some other time I can talk to you about this. There’s all kinds of neuropsychological reasons I find this really interesting too.

But yeah, I really enjoy talking with you. We could definitely keep talking for a much longer time

Alderman: I appreciate you saying that, man. I enjoy talking with you too.