In poker, we constantly here from coaches and friends that aggression pays off. Its talked about like the key to profits and a doorway to poker success, but 2 Card Confidence has some caveats to show us.

Aggression is one of the most important tools in poker. When you’re aggressive, you can win pots without a hand. And when you’ve built an aggressive image, you’ll get paid off more often when you actually do have a hand.

But how much aggression can you apply profitably? And when does it become too much?

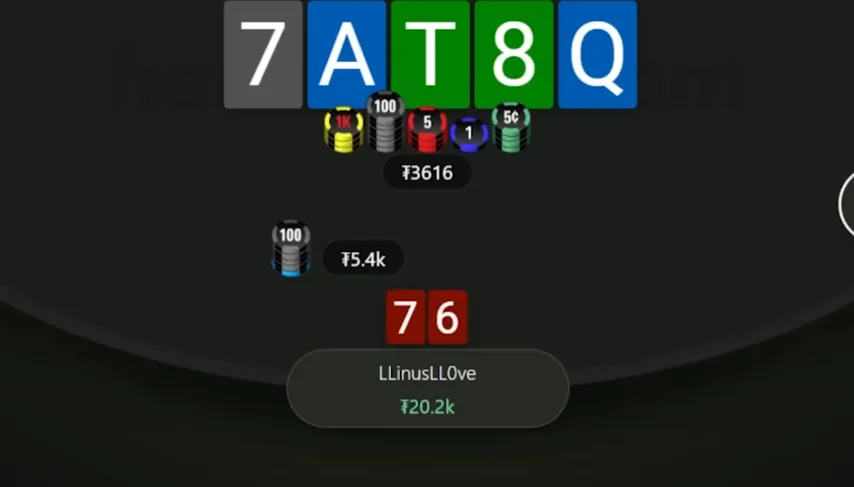

LLinusLLove vs KevinPaque

In this hand, one of the most aggressive players in the game, LLinusLLove, opens from the hijack and gets called by Kevin in the big blind. The flop comes , and Linus fires a full-pot continuation bet.

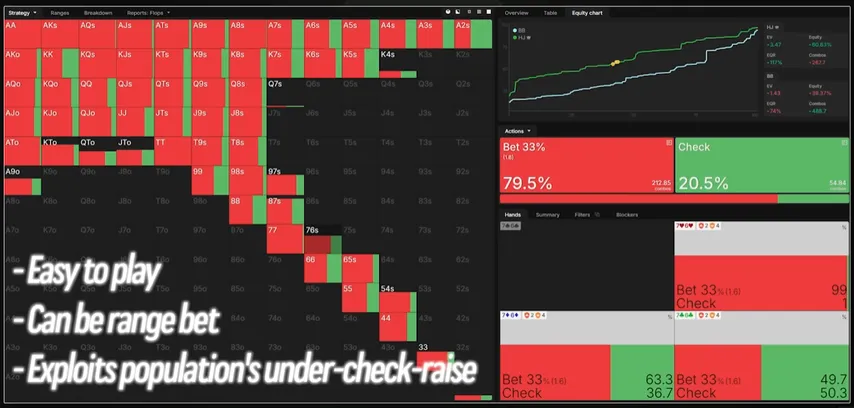

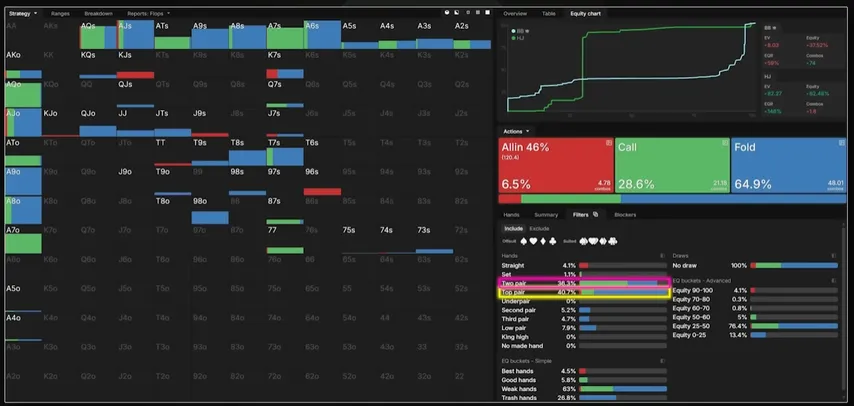

On this type of structure and formation, the solver actually prefers using a big bet size — but as is often the case, it also mixes in smaller bets. If you want to make your life easier in-game, you can simplify by only using one size.

Since all sizes appear in the solver’s mixed strategy, you won’t be losing much EV no matter which one you choose. For small-stakes games, a small bet size is often better — it’s easier to play, can be used as a range bet, and at those stakes, players don’t check-raise against small bets as often as they should. That makes the strategy even more profitable in practice than in theory.

At higher stakes, that mistake doesn’t happen as much. Here, betting big has an extra benefit — it makes Kevin’s life harder than a small bet would. Against a small bet, he can just continue with all third pairs or better, plus every gutshot. But against a pot-sized bet, things change. Now he has to mix between calling, folding, and even raising with underpairs, third pair, and gutshots.

Those hands are indifferent in theory, meaning they have the same EV whether you call, fold, or raise — but in practice, it’s incredibly hard to get those frequencies even close to right.

That’s why from Linus’ point of view, this pot-sized bet is likely forcing a bigger mistake from his opponent than betting small.

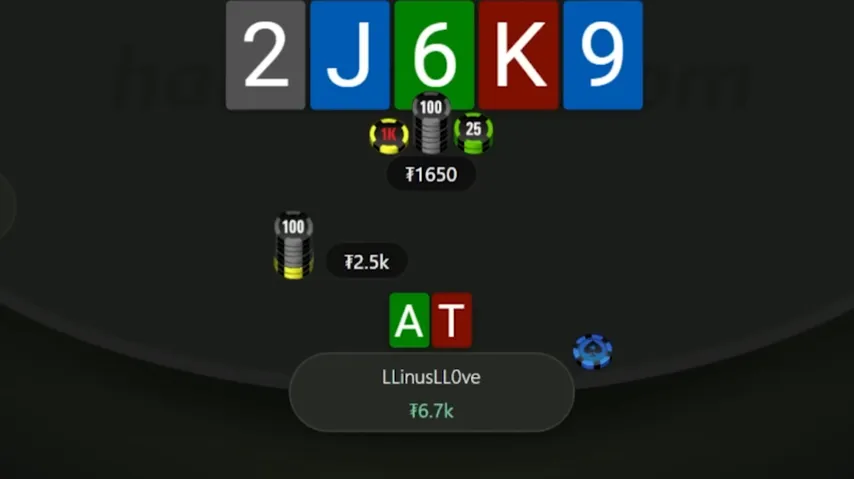

The turn brings a blank ( ), and Linus goes for about 75% of the pot.

The solver agrees — it likes that size or even an overbet with this range. All sets and straights keep betting. So do the best two pairs and top pairs. The solver also keeps barreling with bluffs that have good equity — straight draws, flush draws, or a straight draw plus a pair. Having a pair is valuable: not only do we gain outs to improve against Kevin’s calling range, but we also block some of his strongest hands, like two pair and sets.

Even though a pair is technically ahead of some of Kevin’s holdings, it’s rarely strong enough to just check and win at showdown. Betting also folds out a lot of better hands — third pairs, some second pairs, and even some weak top pairs.

On the river , Linus keeps applying maximum pressure. The solver actually prefers an even bigger sizing here — jamming all-in. At this point, the big blind should be very capped in the number of nut hands he has (like for the straight), especially after facing a pot-sized flop c-bet and another big turn barrel.

Meanwhile, Linus still has plenty of nut combos in his range. Other strong hands like , , or other sets, are unlikely to be in Kevin’s range because they often check-raise earlier streets. That makes them very rare by this point.

Linus’ is a great bluff candidate — it still blocks some two-pair and set combinations, reducing the chance Kevin holds a strong hand.

But why does Linus choose a 150% pot bet instead of going all-in? Of course, we can’t know for sure, but the solver gives us clues. Against a jam, Kevin’s GTO response is relatively straightforward: fold most top pairs, always call with straights and sets, and mix with some two pairs.

But against a 1.5x pot bet, his job becomes much harder. He’s supposed to call a little more often with top pairs, call two pairs about two-thirds of the time, and even incorporate a complex check-raising strategy — sometimes raising sets, always raising straights, and finding the correct bluff combos to check-raise with.

That’s a much tougher tree to navigate. In practice, most players won’t find the right raises or the correct balance of calls and folds — making this 150% pot bet even more profitable than a jam.

This is aggression that mostly aligns with GTO — with perhaps a small exploitative twist.

LLinusLLove vs PR0DIGY

A clearer example of exploitative aggression appears in this next hand.

LLinusLLove opens the button with and PR0DIGY defends his big blind on a rainbow flop. Linus checks back — a line that GTO approves, even though it’s relatively rare with this exact hand.

At lower stakes, simplifying to a small range bet here might be better, but checking does open up a chance to exploit some of the population’s biggest mistakes.

When the big blind checks this spot, population data shows a clear trend: they overfold to delayed c-bets. That makes delayed bluffing especially profitable. This isn’t equilibrium-approved aggression, but if you know your opponent will overfold, you don’t need equilibrium to make money.

In fact, population data shows that at mid and low stakes, players overfold by about seven percentage points on queen- and jack-high boards in this exact situation. That’s huge. Bluffing more than GTO recommends here will earn you extra EV.

This is one of the simplest ways to boost your win rate — identifying spots where players fold too much or call too much and adjusting accordingly. If you know where you can over-bluff profitably and where value betting gets paid more often, EV naturally flows toward you.

Lower aces like through , which GTO would never bluff here, suddenly become pure bluffs.

But ? That still checks. Why? Because has enough showdown value against the hands the big blind checks down, like weaker holdings. It’s one of the last hands you’d add to your bluffing range.

Only if the big blind overfolds by 12 percentage points does start to become as profitable to bet as it is to check. But that would require PR0DIGY to fold a massive portion of his range — essentially folding 70% of his third- and fourth-pair hands right away. That seems unlikely at this level.

On the river, Linus doubles down on aggression — but here’s where it gets dicey. For the solver, is never a bet. It’s a clear check. Betting only works if PR0DIGY dramatically overfolds river check-calls after defending the turn — a big assumption to make against a sharp, balanced opponent.

And this is where too much aggression crosses the line from exploitative to exploitable. GTO shows that hands like , , or weak virtually never check-call rivers here. But if Linus is betting — and perhaps betting 25% of the time — a sharp player like PR0DIGY could counter by printing EV with thin check-calls.

That’s the danger: against opponents who can quickly adjust, hyper-aggressive deviations risk backfiring.

Unfortunately for Linus, PR0DIGY is exactly that kind of opponent.