DavyJones is one of the most feared players at high stakes. He’s incredible at playing against other top regulars. Davey has spent years battling tough regs and sustaining win rates of seven to nine big blinds per hundred hands — something almost no one can do. But as we’ll see later, he also knows how to maximally profit against weaker players. That’s because he’s a master of one of the most important skills in poker: adaptation.

To compete with elite players, you need a solid GTO foundation. But to win seven or eight big blinds against tough regulars, you need something more — you need to be able to adjust your strategy based on who you’re facing. And to make adapting easier for you, this video will focus on two questions you can ask yourself in-game to help make better decisions and get closer to that elite win rate.

Example Number One

In this hand with a , DavyJones opens from the cutoff with and Chris calls in the big blind.

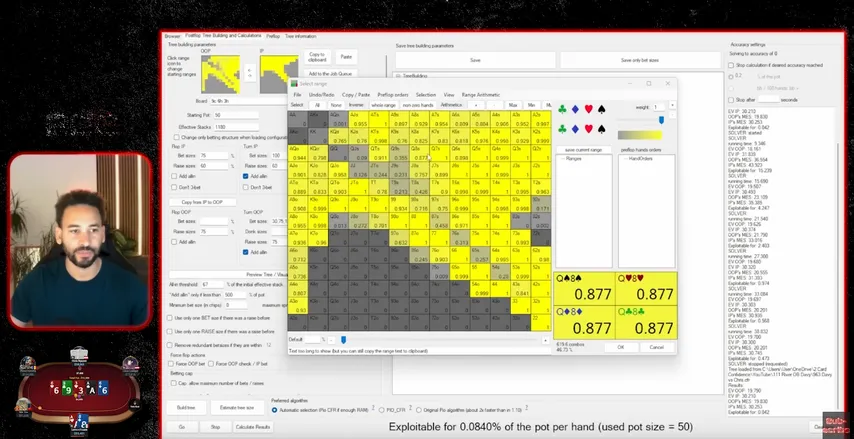

DavyJones c-bets a large 75% pot size — which also happens to be the solver’s preferred sizing here for both his range and his specific hand.

Chris calls, and the turn brings an . Here, the solver would continue betting big — pot-sized if it could only choose one option — and Ace-8 (DavyJones’s hand) along with most other Ax combos are good enough to always or almost always value bet again.

However, DavyJones checks and the river is a . Chris now goes for an overbet.

If you’re playing mid-stakes or lower, this is a spot where the average opponent deviates significantly from GTO. That means you can punish them by adjusting — and in doing so, increase your win rate. I lay everything out in an article you can download for free (link below), where I break down exactly how the population plays this spot incorrectly and how you can exploit them.

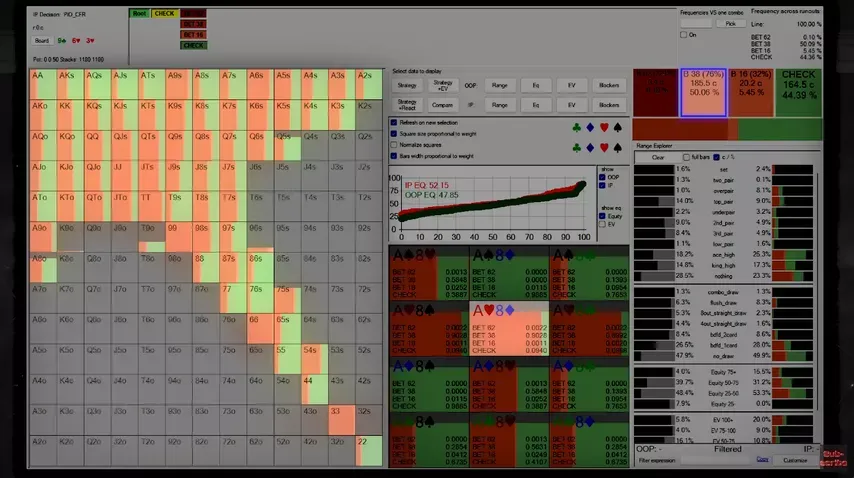

According to the solver, DavyJones’s hand — Ace-8 — is among the top 10% of his range on this river. That makes this a clear, automatic call in theory. So, why doesn’t DavyJones snap it off? It’s not that DavyJones doesn’t know this should be a GTO call. It’s that he’s adapting away from GTO and toward a strategy more fitting against human opponents.

Here’s the logic: for Ace-8 to be a call here, at least one of two things needs to be true.

- Chris needs to have enough bluffs in his range

- Chris needs to have enough value hands worse than Ace-8 that would still overbet

According to the solver, a lot of weaker Ax hands (like Ace-4, Ace-5) would actually overbet here on the river. But let’s break this down. Ace-8 doesn’t even beat those; it only splits. And in practice, most players don’t overbet thin value hands like Ace-4 often enough. Instead, they’d either bet smaller or check behind. That makes the second condition (worse value bets) much weaker in reality than in theory.

That brings us to the most important factor: the bluffs. This is where the two questions I mentioned earlier come into play. When you face a big river bet like this, ask yourself: how many hands that would be bluffs on the river are even in my opponent’s preflop range? And of those, how many actually make it to the river this way?

At first glance, it looks like Chris could have tons of bluffs — missed straight draws, missed flush draws, overcards, etc. But let’s think about it.

Preflop, Chris certainly has a wide big blind calling range, which includes lots of hands that could be bluffs by the river. But how many of those realistically reach the river?

- Overcards: many of those don’t check-call the flop in the first place.

- Strong draws: if Chris is at all aggressive, he’ll have a check-raising range on the flop.

That means many flush draws, combo draws, and strong straight draws get check-raised early, not check-called.

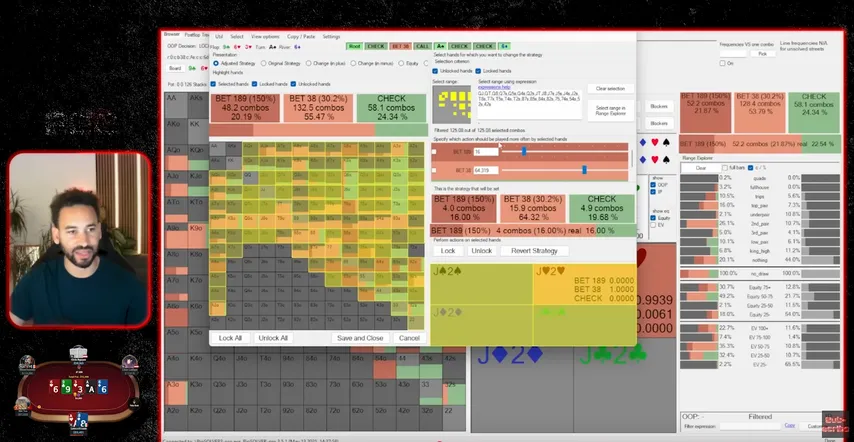

If Chris is even slightly more aggressive than GTO on the flop — which is common at these stakes — it drastically reduces the number of bluffs left in his river betting range. To visualize this, we can simulate what happens if Chris check-raises more often on the flop with hands like combo draws (24.5% GTO → bump to 75%) and high flush draws (11% GTO → bump to 40%). These are realistic population adjustments for many live and online players.

We don’t even need to touch open-ended straight draws, gutshots with backdoor flush draws, or weak pairs. Just increasing the check-raise frequency of combo draws and strong flush draws significantly changes the river range composition. After running this adjustment, the number of bluffs left in Chris’s river betting range plummets. The EV of calling with Ace-8 drops dramatically — from a solid 4BB winner to a marginal or losing call. And suddenly, folding Ace-8 — which looks “crazy” if you only think in GTO terms — becomes exploitatively correct.

This is the essence of DavyJones’s strategy: against a solver-perfect opponent, Ace-8 is a slam-dunk call. Against a real opponent who over-check-raises draws early and under-bluffs rivers, folding becomes optimal.

This is how DavyJones wins at the highest levels — by combining deep GTO knowledge with population-based and player-specific exploits.

Example Number Two

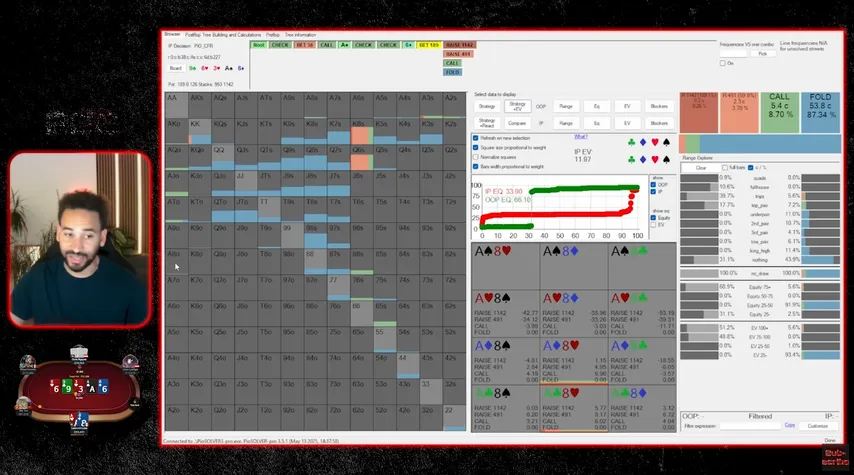

In other hands, though, when circumstances call for it, DavyJones isn’t afraid to adjust away from GTO and play looser than the solver recommends. For example, in one hand, Linus barrels through and DavyJones makes a non-solver-approved call with Ace-8. Why might that make sense?

Think back to our framework.

Linus’s preflop range on the button is wide and includes many hands that end up as pure air on this runout. And in this particular line — bet small on the flop, big on the turn, jam on the river — there aren’t many alternative ways for him to play those hands.

Compared to the Chris hand we looked at earlier, where there were options like check-raising the flop or changing river sizing, Linus’s line doesn’t give him as much flexibility.

That means more bluffs can make it to the river, and calling becomes more reasonable.

And lastly, we see the most extreme form of adapting — and often the most profitable.

Example Number Three

Here, GTO says the only option is to shove — the big blind has less than two-thirds of the pot behind, and any smaller bet size would make no theoretical sense. But this isn’t GTO land — it’s real life, against a recreational player. Against regs, we want balanced bet sizes close to GTO. Against recs, we don’t need balance at all, because they won’t adjust correctly — if they adjust at all. So instead of defaulting to theory, we pick the one size that makes the most money.

And that’s where hand reading comes in. The check-raise on the flop plus the pot-sized turn bet tells us this opponent is polarized — likely a queen or a big draw.

He probably doesn’t have a king; players don’t often pot the turn with a one-pair king after a flop check-raise.

By the river, when he checks, what’s left? If he had a queen, most regs just shove. So if he’s checking, it’s likely missed draws or weak pairs trying to get to showdown. Maybe hands like Ace-Ten, Ace-Jack, Jack-Ten, or some backdoor flush draws.

And that’s why DavyJones does something brilliant: instead of shoving, he bets tiny — just 10K. This size looks absurd in solver land, but against a rec it’s genius. Why? Because it actually gets called by the weak Ace-highs, pocket pairs, or random 5x hands that would fold to a shove. It even leaves room for the opponent to turn their hand into a bluff-check-raise. Against a queen, you get called anyway. Against anything worse, this is the only size likely to earn more money.

This sizing doesn’t exist in GTO. But in real life, against non-GTO opponents, this might actually be the “real GTO” — the size that maximizes profit.